By Suzanne Norquist

When I prepared to make some videos for a project, my twenty-six-year-old daughter said, “Oh, Mom, we need to do something about those eyebrows.”

Not a new concept, but what is considered the perfect brow? Thick? Thin? Arched? Unibrow? And how is perfection achieved?

Answers to these questions have varied throughout history. Ancient Egyptians desired bold, prominent brows—like a god would have. Ancient Greeks and Romans believed unkempt eyebrows showed purity, and unibrows were prized. In the Middle Ages, hairy brows distracted from the natural beauty of the forehead. Therefore, women sculpted and plucked them away.

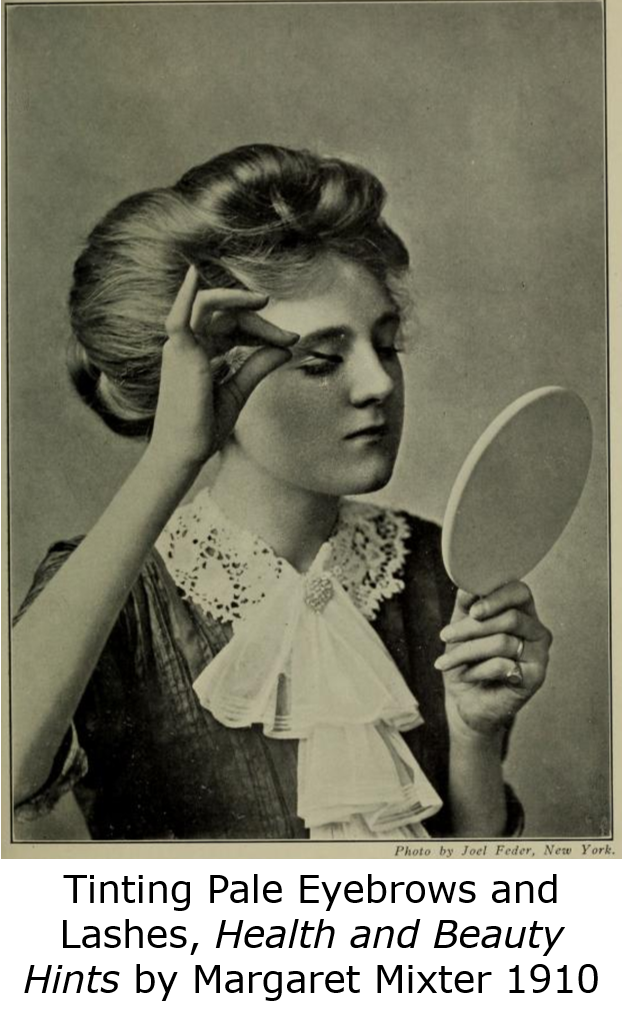

Smaller, more shapely brows persisted into the early 1900s. In her 1910 book, Health and Beauty Hints, Margaret Mixter describes the perfectly shaped brow as “a swallow’s wing, the line long and sweeping, the hair short and thick without being coarse.”

Margaret Mixter recommended conditioning and training. Generally, some kind of oil was used. Here is her recipe for Eyebrow and Lash Tonic:

Red Vaseline, 5 grams; Boric acid, 10 centigrams. Make into a smooth paste, and massage into the brows at night, also rubbing lightly on the lashes at the roots.

Vaseline has been a well-known brand since 1870, and the pink version is still available today. Boric Acid has mild antiseptic, antifungal, and antiviral properties.

Massaging eyebrows every night could improve their health, and a soft brush helped shape them.

Coloring wasn’t encouraged, particularly with permanent colors, which would damage the hair. A blackened piece of burnt cork or some Indian ink could darken them a little if needed.

Trimming the eyebrows was never recommended, as it would create a coarse, unkempt look. Nor was plucking. The 1910 beauty book suggests electrolysis for hair removal.

Early versions of electrolysis would make me nervous. It was invented in 1875, and commercial machines became available in 1900. By the early 1900s, schools of electrolysis and dermatology were popping up.

In this 1898 advertisement, Professor Newby explains the benefits of electrolysis. Not only could he take care of skin blemishes and superfluous hair, but he also specialized in rheumatism, paralysis, tumors, and cancer. He used the latest electrical scientific discoveries.

What women wouldn’t endure in the name of fashion.

Eyebrows are just one aspect of an attractive expression. The beauty book also gives some advice related to eyelashes, mostly a little conditioning and trimming.

In antiquity, long, lush lashes represented youth and fertility. Burnt cork or coal often created the effect. By the Middle Ages, too much hair was viewed as erotic, and lashes were plucked. That trend didn’t last for long. Versions of mascara existed in the 1800s.

Artificial eyelashes made an appearance in the late 1800s when Parisian women sewed hairs on their eyelids for enhancement. And, of course, everyone adopts Paris fashions. An article in an 1897 newspaper in Telluride, Colorado, describes the procedure for sewing human hair to the eyelids to extend the lashes.

Beauticians experimented with different varieties of false lashes. In 1903, the New York Press reported, “In a hair store on Broadway, a novelty item is being sold in the shape of long, luxuriant eyelashes, which can be adjusted in two minutes and will wear for one month. They cost $3 a pair.”

They probably weren't sewn on if they could be adjusted that quickly.

The first patent for glue-on artificial lashes was awarded to Anna Taylor, a Canadian woman, in 1911. However, falsies didn’t really become popular until 1916, when actress Seena Owen wore them in the movie Intolerance.

Crazy enough, I can barely see the eyelashes in the picture above. Perhaps without them, her eyes completely disappeared.

Beauty trends for brows and lashes haven’t changed much in the last hundred years. Most of us don’t cringe anymore, as these treatments have been refined and are commonplace.

And, who am I to criticize? I wear mascara for a day of hiking in the mountains. All women want to put on their best face.

***

”Mending Sarah’s Heart” in the Thimbles and Threads Collection

Four historical romances celebrating the arts of sewing and quilting.

"Mending Sarah’s Heart" by Suzanne Norquist

Rockledge, Colorado, 1884

Sarah seeks a quiet life as a seamstress. She doesn’t need anyone, especially her dead husband’s partner. If only the Emporium of Fashion would stop stealing her customers, and the local hoodlums would leave her sons alone. When she rejects her husband’s share of the mine, his partner Jack seeks to serve her through other means. But will his efforts only push her further away?

For a Free Preview, click here: http://a.co/1ZtSRkK

Suzanne Norquist is the author of two novellas, “A Song for Rose” in A Bouquet of Brides Collection and “Mending Sarah’s Heart” in the Thimbles and Threads Collection. Everything fascinates her. She has worked as a chemist, professor, financial analyst, and even earned a doctorate in economics. Research feeds her curiosity, and she shares the adventure with her readers. She lives in New Mexico with her mining engineer husband and has two grown children. When not writing, she explores the mountains, hikes, and attends kickboxing class.

She authors a blog entitled, Ponderings of a BBQ Ph.D.